American Madness

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

On the night of June 17, 1998, a Cornell campus police officer named Ellen Brewer had just begun her shift when she noticed a tall, silhouetted figure moving slowly across the engineering quad. The man appeared to be dressed all in black. Brewer felt a whisper of danger. She slowed her car, and the shrouded figure began loping toward her. He raised a hand and hailed her as if she were a taxi driver. As he drew closer, she thought he must have been the victim of an assault, perhaps in need of medical assistance.

Suddenly, as if in a single stride, the man was at her window. He lowered his face, shiny with sweat, close to hers. He was muttering incoherently; his rust-colored beard and hair were wildly matted. He seemed to be saying that he might have killed someone, his girlfriend or perhaps a windup doll. Brewer radioed in the strange encounter, requested backup, and got out of her car.

She thought again that the disoriented man, whose clothes were bloody, had been attacked or maybe had fallen into one of the steep gorges that famously intersect the campus, but when she tried to steer him out of the road, he leaped back, a large hand clenched into a fist.

The police station was all of 100 yards away, on Campus Road, and officers were already coming toward them, some on foot, others in cars. They escorted the man, whose name was Michael Laudor, to Barton Hall, the looming stone fortress that the campus police shared with the athletics department.

Once inside, Michael didn’t need much prodding to answer questions, but whenever he mentioned possibly harming his girlfriend, whom he sometimes referred to as his fiancée, he added, “or a windup doll.”

When Sergeant Philip Mospan, the officer in charge that night, asked Michael if he was hurt, he received a simple no. In that case, “where did the blood all over your person come from?” Michael told him it was Caroline’s blood.

“Who is Caroline?” the sergeant asked.

“She’s my girlfriend,” Michael said. “I hurt her. I think I killed her.”

Was Michael sure about that?

He thought so, but asked, “Can we check on her?”

His concern seemed urgent and genuine, though puzzlingly he said this had happened in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, 220 miles away.

Mospan prefaced his request to the Hastings-on-Hudson dispatcher by saying, “This may sound off the wall …” Because who kills someone in Westchester County, drives to Binghamton, and takes a bus to Ithaca, as Michael said he had done, only to surrender to campus police? The dispatcher asked him to wait a moment, and then a detective came on the line. “Hold him!” the detective said. “He did just what he said he did.” They had people at the apartment. The woman was dead, the scene ghastly.

And so it was that my best friend from childhood, who had grown up on the same street as me; gone to the same sleepaway camp, the same schools, the same college; competed for the same prizes and dreamed the same dream of becoming a writer, was arrested for murdering the person he loved most in the world.

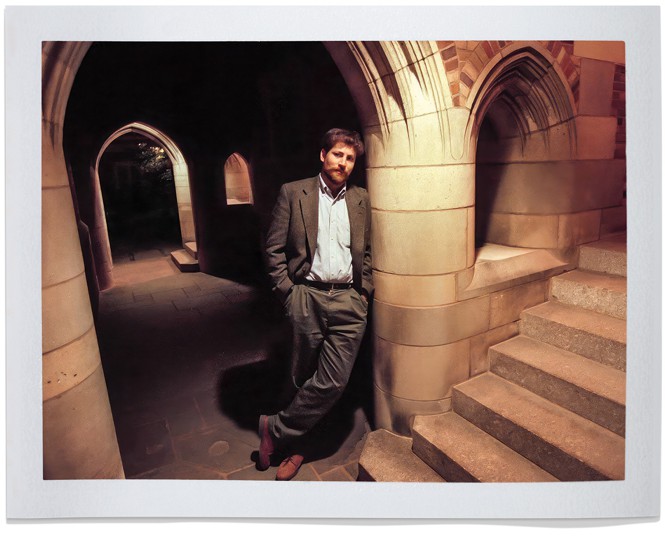

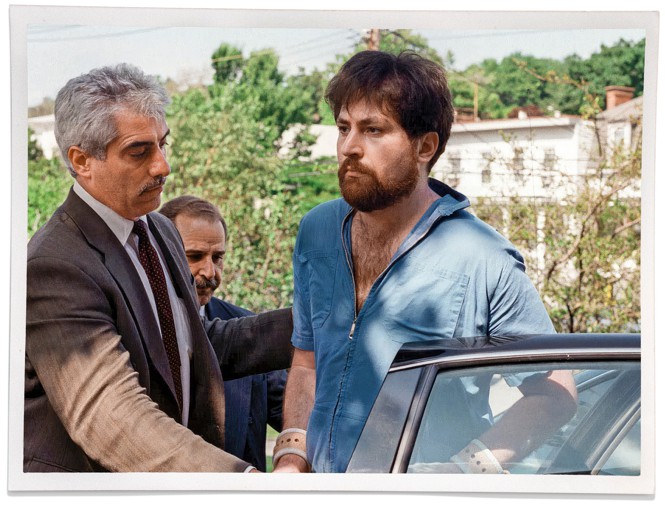

When police officers from Hastings-on-Hudson showed up the next morning to bring Michael back there, they were surprised to find reporters, photographers, and TV cameras waiting outside the Ithaca jail. Jeanine Pirro, then the Westchester district attorney, who charged Michael with second-degree murder, would call him “the most famous schizophrenic in America,” a perverse designation, though strangely in tune with the aura of specialness that had characterized so much of his life, and that had shaped the expectations we’d grown up with. Michael was famous for brilliance. He’d gone to Yale Law School after developing schizophrenia, and was called a genius in The New York Times, which led to book and movie deals. Brad Pitt was attached to star.

Michael’s friends and family and his supporters at Yale had thought intelligence could save him, allow him to transcend the terrible disease that was causing his mind to detach from reality. Michael was arrested on a campus where he’d spent six happy weeks at an elite program for high-school kids in the summer of 1980, when we were 16. I sometimes wondered if he was trying to get back to a time when his mind was his friend and not his enemy, but a forensic psychiatrist who examined Michael for the prosecution set me straight: Michael thought his fiancée was a “nonhuman impostor” bent on his torture and death, and in his terrified delusional state, he had fled hours to Cornell hoping to evade destruction and call the police. In other words, he was seeking asylum.

Asylum was also what Michael needed in the months before he killed Carrie. Not “an asylum” in the defunct manner of the vast compounds whose ruins still dot the American landscape like collapsing Scottish castles, but a respite from tormenting delusions—that his fiancée was an alien, that his medication was poison. Because he was very sick but did not always know it, Michael had refused the psychiatric care that his family and friends desperately wanted for him but could not require him to get.

[Thomas Insel: What American mental-health care is missing]

Michael needed a version of what New York City Mayor Eric Adams called for in November, when announcing an initiative to assess homeless individuals so incapacitated by severe mental illness that they cannot recognize their own impairment or meet basic survival needs—even if that means bringing them to a hospital for evaluation against their will. “For too long,” Adams proclaimed, “there’s been a gray area where policy, law, and accountability have not been clear, and this has allowed people in need to slip through the cracks. This culture of uncertainty has led to untold suffering and deep frustration. It cannot continue.”

Though 89 percent of recently surveyed New York City residents favored “making it easier to admit those who are dangerous to the public, or themselves, to mental-health facilities,” attacks on the mayor’s modest adjustments to city policy began immediately. News stories suggested that a great roundup of mentally ill homeless people was in the offing. “Just because someone smells, because they haven’t had a shower for weeks,” Norman Siegel, a former head of the New York Civil Liberties Union, told the Times, “because they’re mumbling, because their clothes are disheveled, that doesn’t mean they’re a danger to themselves or others.”

Never mind that these were not the criteria outlined in the Adams plan. Paul Appelbaum, the director of the Division of Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia, says that the government has an interest in protecting people who are unable to meet their basic needs, and that he believes the mayor’s proposal has been largely misunderstood. “There’s an intrinsic humanitarian imperative not to stand by idly while these people waste away,” Appelbaum recently told Psychiatric News.

The people Adams is trying to help have been failed by the same legal and psychiatric systems that failed Michael. They all came of age amid the wreckage of deinstitutionalization, a movement born out of a belief in the 1950s and ’60s that new medication along with outpatient care could empty the sprawling state hospitals. Built in the 19th century to provide asylum and “moral care” to people chained in basements or abandoned to life on the streets, these monuments of civic pride had deteriorated over time, becoming overcrowded and understaffed “snake pits,” where patients were neglected and sometimes abused. Walter Freeman, notorious for the ice-pick lobotomy (which is exactly what it sounds like), was so horrified by the naked patients crammed into state hospitals, shockingly featured in a famous 1946 Life article, that he developed a new slogan: “Lobotomy gets them home.”

[Read: The truth about deinstitutionalization]

But getting people home was never going to be a one-step process. This would have been true even if the first antipsychotic medications, developed in the ’50s, had proved to be a pharmaceutical panacea. And it would have been true even if the neighborhood mental-health clinics that psychiatrists had promised could replace state hospitals had been adequately funded. During the revolutions of the ’60s, institutions were easier to tear down than to reform, and the idea of asylum for the most afflicted got lost along with the idea that severe psychiatric disorders are biological conditions requiring medical care. For many psychiatrists of the era, mental illness was caused by environmental disturbances that could be repaired by treating society itself as the patient.

The questions that should have been asked in the ’60s, and that might have saved Michael and Carrie, are relevant to Mayor Adams’s policies now: Will there be follow-up care, protocols for complying with treatment, housing options with supportive services and a way to fund them? Will there be psychiatrists and hospital beds for those who need them? But it would be ironic if all of the past failures at the federal, state, and local levels became an argument against making a first small step toward repair.

If I had known Michael only as he appeared grimly on the front pages of the tabloids 25 years ago, or Caroline Costello as half of a smiling picture all the more tragic for being so full of innocence and hope, I would not have understood how much is at stake in the current efforts to improve the care given to people with severe mental illness. Neither Adams’s policies—nor the more comprehensive measures advanced by Governor Gavin Newsom, in California—will bring about a sweeping transformation; only incremental changes, and many accompanying efforts at all levels of government, will make a difference. And these will not be possible without a shift in the way people think about the problem.

Now when I think about the frenzied moments before Michael killed Carrie, when violence was imminent and intervention was necessary but impossible, I understand that it isn’t on the brink of crisis but earlier that something can be done—though only by a culture that is capable of making difficult choices and devoting the resources to implement them.

But I knew Michael before he thought Nazis were gunning for him. I knew him before the lurid headlines, the Hollywood deal, the publishing contract, and the New York Times profile that proclaimed him a genius. I knew him as a 10-year-old boy, when I was also 10 and he was my best friend.

The Cuckoo’s Nest

I met Michael as I was examining a heap of junk that the previous owners of the house we had just moved into in New Rochelle had left in a neat pile at the edge of our lawn. It was 1973. A boy with shaggy red-brown hair and large, tinted aviator glasses walked over to welcome me to the neighborhood. He was tall and gawky but with a lilting stride that was oddly purposeful for a kid our age, as if he actually had someplace to go.

His habit of launching himself up and forward with every step, gathering height to achieve distance, was so distinctive that it earned him the nickname “Toes.” He was also called “Big,” which is less imaginative than “Toes,” but how many kids get two nicknames? And Michael was big. Not big like our classmate Hal, who appeared to be attending fifth grade on the GI Bill, but big through some subtle combination of height, intelligence, posture, and willpower.

Even standing still, he would rock forward and rise up on the balls of his feet, trying to meet his growth spurt halfway. He stood beside me on Mereland Road in that unsteady but self‑assured posture, rising and falling like a wave. He was socially effective in the same way he was good at basketball—through uncowed persistence. I often heard in later years that people found him intimidating, but for me it was the opposite. Despite my shyness—or because of it—Michael’s self‑confidence put me at ease. I fed off his belief in himself.

Was Michael bouncing a basketball the day I met him? He often had one with him, the way you might take a dog out for a walk. I’d hear the ball halfway down the block, knocking before he knocked.

Even today, when I hear the taut report of a basketball on an empty street, the muffled echo thrown back a split second later like the after-pulse of a heartbeat, I have a visceral memory of Michael coming to fetch me for one‑on‑one or H‑O‑R‑S‑E, or simply to shoot around if we were too deep in conversation for a game or if I was tired of losing.

Michael might just as easily have had a book the day he introduced himself. He often had several tucked under one arm, and he would dump them unceremoniously at the base of the schoolyard basketball hoop. It was always an eclectic pile: Ray Bradbury, Hermann Hesse, Zane Grey Westerns, books his father assigned him—To Kill a Mockingbird or a prose translation of Beowulf—stirred in with the Dune trilogy and Doc Savage adventures.

Our fathers were both college professors, but Michael’s father, who taught economics, sported a leather bomber jacket and spoke in a booming Brooklyn manner. My father, who taught German literature, wore tweed jackets from Brooks Brothers, spoke with a soft Viennese accent, and named me and my sister for his parents, who had been murdered by the Nazis.

Michael had all four grandparents, something I’d seen only in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. They did not all sleep in one bed, like Charlie’s grandparents, but he saw a lot of them. His Russian-born grandparents still lived in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, where his father had grown up and his grandmother Frieda had stuffed money into a hole in the bathroom wall until a plumber came and stole it one day. Michael recounted stories about “crazy” Frieda with such amused affection that it was a shock when he told me, years later, that she had schizophrenia.

Every weekday morning during the school year, I’d walk to the bottom of our one‑block street, ring Michael’s bell, and wait for him to step groggily out from the household chaos. We’d hike up the hidden steps behind his house that led to the basketball court, climb a second flight of outdoor stairs, and slip into the school through a side door that felt like a private entrance.

Thanks to Michael, I became a big fan of Doc Savage, originally published in pulp-fiction magazines in the 1930s but reissued as cheap paperbacks starting in the ’60s. We joked about the archaic language and dated futurisms—long‑distance phone calls!—but Doc Savage, charged with righteous adrenaline, formed an important part of the archive of manly virtues that I received secondhand from Michael, who got them wholesale from his father, his grandfathers, old movies, and assorted dime novels.

Like Doc Savage, Michael had a photographic memory. He also read at breakneck speed. I was a fast talker but a slow reader; Michael burned through the assigned reading with such robotic swiftness that he was allowed to read whatever he wanted to, even during regular class time.

He kept stacks of paperbacks on his desk at school, working his way through fresh piles every day. He didn’t just read the books; he read them all at the same time, like Bobby Fischer playing chess with multiple opponents. After a few chapters of one, he’d reach for another and read for a while before grabbing a third without losing focus, as if they all contained pieces of a single, connected story.

I was a direct beneficiary of all that reading. He seemed to have almost as much of a compulsion to tell me about the books as he did to read them, and I acquired a phantom bookshelf entirely populated by twice-told tales I heard while we were shooting baskets, going for pizza, or walking around the neighborhood.

Michael’s precocity made him seem like someone who had lived a full life span already and was just slumming it in childhood, or living backwards like Benjamin Button or Merlyn. My parents were amused by the speed with which he took to calling them Bob and Norma, and the ease with which he held forth on politics while I waited for him to finish so we could play Mille Bornes or go outside. I knew that the president was a crook—but Michael knew who Liddy, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman were and what they had done, matters he expounded as if Deep Throat had whispered to him personally in the schoolyard.

Michael also saw more R-rated movies than I did. In 1976, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which was about a sane wiseass named Randle McMurphy locked in a mental hospital by a crazy culture, won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Michael explained that the hospital tries drugging McMurphy into submission and shocking his brain until his body writhes, then finishes him off with a lobotomy, all because he won’t behave.

I’d never heard of a lobotomy, but Michael assured me it was real; they stuck an ice pick in your head and wiggled it until you went slack like a pithed frog, docile enough to be dissected alive. This was a far cry from the “delicate brain operation” that Doc Savage performed on criminals to make them good so they would not have to rot in prison.

The lobotomy in Cuckoo’s Nest reduces McMurphy to zombie helplessness. His friend Chief Bromden smothers him to death with a pillow and escapes out a window so the other inmates will still have a hero to believe in. Like a lot of things in the ’70s, the movie sent a mixed message, exposing the abuses of psychiatric hospitals while justifying the killing of a mentally impaired person.

The summer before college, I found myself filled with optimism. I’d always been the tortoise to Michael’s hare, but we both got into Yale, and for the ninth year in a row we would be going to the same school. I was surprised when Michael told me one afternoon, as we lounged on my parents’ patio, that he did not think we would see much of each other at Yale. When I asked him why, he told me that I was simply too slow.

We did see less of each other in college, but when I’d run into Michael on Metro-North, heading home for vacation, we’d talk in the old way, nonstop until New Rochelle.

Impatient as always, Michael decided to graduate in three years. He also informed me that he had decided to become rich, as if that were something you could declare like a major. He had been recruited by a Boston-based management consulting firm called Bain & Company, a place, he explained, where the supersmart became the superrich.

He was ironic about his choice to join the ranks of the young, upwardly mobile philistines the media had taken to calling yuppies, but wanted me to know that he was not abandoning intellectual or artistic aspirations: His plan was to spend a decade making gold bricks for Pharaoh, after which he would buy his freedom and become a writer.

I lost track of Michael during his time at Bain, though once or twice I’d hear my name on Mereland Road while home for a visit. Turning, I’d see him loping up the hill, grinning as if we were still fifth graders and his fancy trench coat was a costume.

But I learned later that he was having a rough time. The pressure at Bain was constant. Michael began complaining that his heart raced, his digestion was bad, and Machiavellian higher‑ups were “out to get him” but would never let him go because of his value to the firm, which seemed unlikely even for a place known as “the KGB of the consulting world.” He quit Bain in 1985 and began writing in earnest—the 10-year plan had become a one-year plan. Even after he quit, Michael thought his phone was being tapped and Bainies were spying on him.

Still, his life sounded like the fulfillment of a dream. He was living in the attic of a grand house with a private beach at the south end of New Rochelle owned by the parents of a friend. The mansion might have drifted north and west from the gilded north shore of Long Island. Michael called it “the Gatsby House” and claimed that he could see a green light glinting far out on the water as he stayed up late, writing stories and staring into the night. He wanted to be Fitzgerald and Gatsby both, the dreamer and the dream. Didn’t we all?

The friend’s parents happened to be Andy and Jane Ferber, community psychiatrists who had dedicated their life to liberating people with severe mental illness from state institutions. The Ferbers were at the center of an overlapping collection of friends and colleagues who referred to themselves as “the Network,” drawn together by their experience in community psychiatry and a sincere desire to leave the world better than they’d found it.

They’d been inspired by the Scottish psychiatrist R. D. Laing, who called insanity “a perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world,” and books such as Asylums, Erving Goffman’s 1961 landmark study that focused on the impact psychiatric institutions had on the behavior and personality of patients rather than on the illnesses that sent them there. A sociologist, Goffman frequently put the term mental illness in quotation marks, though he abandoned the practice in later writing, after his wife’s suicide.

Most of the Network had met in the ’60s, when President John F. Kennedy had vowed to replace the “cold mercy of custodial isolation” with the “open warmth of community concern.” The Community Mental Health Act of 1963, which Kennedy signed on October 31 of that year, promised that an “emphasis on prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation will be substituted for a desultory interest in confining patients in an institution to wither away.” It was the institution’s turn to wither away, replaced by the sort of communal care offered by the center that Jane Ferber had run in downtown New Rochelle, with its workshops, visits to patients in board-and-care facilities, and drop-in services.

One problem was that nobody knew how to prevent severe mental illness; another was that rehabilitation was not always possible, and could only follow treatment, which was easily rejected. And despite having been created to replace hospitals caring for the most intractably ill, community mental-health centers, as their name suggested, aimed to treat the whole of society, a broad mandate that favored a population with needs that could be addressed during drop-ins. “It wasn’t that we weren’t interested in dealing with difficult cases,” writes the psychologist Roger B. Burt, looking back at the community center he ran in Baltimore in the late ’60s, but that he and his idealistic colleagues feared that “to blindly accept ‘dumping’ [of severely ill patients from the old asylums] would have bled the staff of time and taken services away from people who would benefit from it.” The only recourse for families caring for severely ill relatives in acute distress was to call the police, who would arrest them.

The police didn’t like this, and who can blame them? They did not sign up to be caretakers of people suffering psychotic episodes. Meanwhile, the most vulnerable members of the community were being criminalized.

The Network’s values were well expressed in Crisis: A Handbook for Systemic Intervention, which Jane Ferber and a colleague had published in the late ’70s, written for mental-health professionals who “feel in some way oppressed by the existence of mental hospitals, jails, reform schools, hierarchical corporations or governments of covert nepotism.”

One of the manual’s case histories described an elderly woman with “regressive psychosis” who had been wandering the halls of her Upper West Side boardinghouse naked. Members of Jane’s team were called in to help get the woman into a nursing home; instead, they coached her on “how to avoid being committed.” They gave her tips like “wear your clothes at all times” and “evacuate in the toilet instead of the floor,” and they reminded her to smile at the nurses “no matter what.”

Keeping people out of the hospital was the hospitals’ policy too, even if it had more to do with legal constraints and available beds than faith in community care. Around the time that Michael moved into the Gatsby house, there were newspaper stories about a woman with schizophrenia named Joyce Brown who had been hospitalized against her will as part of a new program to prevent people from dying on the streets, a sort of precursor to Mayor Adams’s initiative. The program included a broader interpretation of commitment laws and promised appropriate housing upon discharge.

Brown slept on a sidewalk grate; ran into traffic; defecated on herself; screamed racial epithets at Black men (though she was Black herself); and tore up dollar bills, set them on fire, and urinated on them. But a judge ordered her released. He agreed with her lawyers at the New York Civil Liberties Union, headed by Norman Siegel at the time, and said that her behavior was the result of homelessness rather than its cause. Though burning money “may not satisfy a society increasingly oriented to profit‑making and bottom‑line pragmatism,” the judge wrote, Brown’s behavior was “consistent with the independence and pride she vehemently insists on asserting.”

Her sisters, who had struggled to care for Brown in their homes before psychosis, drug abuse, and violent behavior had made it impossible, came to a different conclusion. If the judge believed that a Black woman shrieking obscenities and lifting her skirt to show passersby her naked buttocks was living a life of “independence and pride,” they said after the ruling, he must be a racist who thought such degradation was “good enough for her, not for him or his kind.” If that were his sister on the street, they had no doubt, he “would not stand for it.”

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who had served on President Kennedy’s mental-health task force as a young assistant secretary of labor, had helped draft the report that led to the Community Mental Health Act. Years later, as a U.S. senator representing New York, he looked back with deep regret. In a 1989 letter to the Times, written in a city “filled with homeless, deranged people,” he wondered what would have happened if someone had told Kennedy, “Before you sign the bill you should know that we are not going to build anything like the number of community centers we will need. One in five in New York City. The hospitals will empty out, but there will be no place for the patients to be cared for in their communities.” If the president had known, Moynihan wrote, “would he not have put down his pen?”

The Locked Ward

While I was studying English literature in graduate school at UC Berkeley, and learning from Foucault that mental illness is a “social construct” invented to imprison enemies of the state, Michael was being hounded by Nazis in New Rochelle. Even if they were imaginary, they ran him off the road when he was driving and tried to run him down when he was walking. Characters from a thriller he was writing stalked him. Even after he burned the novel, he brought a baseball bat into bed with him.

Jane found Michael a psychiatrist from the Network whose intellectual manner appealed to him. He went home to his parents’ house but remained a part of the Network’s extended family.

One cold winter morning before work in 1987, my father saw him in the flapping remnant of his fancy trench coat, walking distractedly up Mereland Road like someone with no place to go in a hurry. My father was waiting outside for his ride to the train station. The closer Michael got, the worse he looked, and my father asked him what was wrong.

I haven’t been well, Michael told him, uncharacteristically laconic. My father was deeply affected by Michael’s drawn and distracted features, his almost palpable aura of affliction. My father wanted to stay and talk more, but his ride arrived. He got in the car with the feeling that he was abandoning someone in crisis.

A few days later, my parents called me. They sounded so grave and strange that I thought my grandmother must have died, but my father said they were calling about Michael Laudor. The formal use of his full name was an acknowledgment of how far apart we’d drifted and a portent of bad news: Michael was in the psychiatric unit of Columbia-Presbyterian.

My mother told me that Michael thought his parents were Nazis, and that he’d been patrolling his house with a kitchen knife. Ruth had been unable to convince Michael that she was his mother and not a Nazi, so she’d locked herself in her bedroom and called the police.

As soon as I got off the phone, I called the Laudors. I still knew the number by heart, though it had been years since I’d dialed it. Michael’s father, Chuck, encouraged me to call Michael, who was up on 168th Street in a locked ward. This was the first time I’d heard that terrible phrase. No phones in the rooms, just a payphone in the corridor.

Sometimes, Chuck said, the doctors gave Michael special drugs, and if he was “tuned in,” he would talk. The notion affected me almost as much as “locked ward.” The idea that someone so verbal needed to be “tuned in” was hard to imagine.

I dialed the number Chuck gave me, and Michael answered in a groggy voice, as if he’d been waiting by the payphone and fallen asleep. I was afraid he wouldn’t recognize me or want to talk—I’d been afraid he wouldn’t be able to talk—but he knew me right away and sounded pleased, in a weary way, that I was on the phone.

His voice was leaden and far off, but I felt the muffled intensity of his familiar presence. “I’ve never been in prison before,” he said ruefully when I asked how he was doing. The “day room” was full of noise and cigarette smoke, the TV on all the time. “I don’t like smoky rooms with televisions,” he told me, “but they say if you want to leave, you have to go there and interact.”

It sounded bleak. Was there nothing else to do?

“Eight a.m. breakfast. Twelve p.m. lunch. Five p.m. dinner.”

It was only after I’d laughed that I realized this might not be deadpan humor, just deadpan delivery. Disconcertingly, I wasn’t sure. Michael hadn’t lost his old way of saying things, and I was still listening with ingrained expectations. Could he still be ironic? Could he still tell a joke?

I wanted to apologize for laughing, but didn’t. I felt Michael’s need to talk, to tell me things more than to converse. He was “tuned in,” as Chuck put it, though to a different frequency from the one I was used to.

“Dr. Ferber says I have a delicate brain,” he told me with a hint of pride that only enhanced the pathos of his abject situation.

I’d called half-hoping that Michael wouldn’t come to the phone, but I heard myself asking if he wanted a visitor. He was eager for one. We agreed that I’d visit on the coming Tuesday. I gave him my phone number in Manhattan and had to repeat each number very slowly.

“It’s hard to work the pen right now,” he said.

A taciturn attendant with keys on a ring like a jailer’s in a movie unlocked the heavy door of Michael’s ward. The door had a small, thick window at eye level. The attendant locked the door behind us, and I felt a clinch of claustrophobia. Locked ward was not a metaphor.

I followed the attendant. Michael was sitting rigidly on his bed, trancelike. His parents, in chairs near the bed, leaped up when I came in. Ruth hugged me hard and Chuck shook my hand. After they left the room to give us a chance to talk, Michael seemed marginally more relaxed, but he was apparently past thinking they were Nazis. He shifted uncomfortably on the bed, an occasional tremor running through his body.

At this point, no one had yet named Michael’s illness for me, saying only that he’d had “a break.” Michael referred to himself as paranoid, but who isn’t? The doctors were giving him drugs, he told me, but not much beyond that. He felt like a television set with bad reception; nobody knew what to do except move the antenna around and bang on one side and then the other, hoping the picture would improve.

Before he wound up in the hospital, he had applied to the top seven law schools in the country. They’d all accepted him, though by then he was in no condition to do anything about it, so he’d asked his brother to reject all of them except Yale, which he deferred for a year.

It was, in a way, a typical Michael story: He had rejected the law schools, not the other way around.

Michael said it was easier to walk than to sit, so we went out into the corridor and walked up and down together. He carried himself with effortful stillness, cautiously erect. At one point he led me to a barred window that looked out over fire escapes, water towers, the windowless back ends of buildings exposed by demolition, things not meant to be seen.

“Look what’s become of me,” he said pitiably, as if he were the view.

Michael volunteered that he could leave whenever he wanted to, because he had—at his father’s urgent insistence—signed himself in. This surprised me, not only because he hated being there but also because of the dramatic story I’d heard about his arrival.

It would not have occurred to me that someone marching around with a kitchen knife might not be considered a danger to himself or others. Michael had carried the knife, and slept with the baseball bat, because he’d thought his parents had been replaced by surgically altered Nazis who had murdered them and wanted to kill him. His psychiatrist considered that defensive, not aggressive, behavior.

The doctors at Columbia-Presbyterian believed he ought to be there. The longer they could keep him, the more time he would have to receive treatment and to heal, a process much slower than the temporary abatement of florid symptoms that medication provided. He was persuaded to stay, or was at least afraid to leave.

Visiting Michael, I found it impossible to pretend that he was suffering from a “social construct.” I disliked the hospital, but even with its heavy locked door, I knew it wasn’t a branch of the “carceral state” devised by a power‑mad society to torment him.

Michael spent eight months in the locked ward at Columbia-Presbyterian, which, he murmured guiltily, cost even more than Yale. His long stay gave his doctors time to find the least incapacitating dose of the powerful drugs that were supposed to have eliminated mental hospitals years before.

Michael’s medication was calibrated carefully enough that he was no longer convinced Josef Mengele was preparing to remove his brain without anesthesia. He had his suspicions, but, as he later said, he’d stopped trying to bash his skull against the sink in a preemptive effort to destroy his own brain. Now when hallucinations came calling, Michael could often recognize them for what they were and “change the channel,” as he put it.

Michael left the hospital to live among the ruins of multiple systems. He would have to continue taking antipsychotic medication, though 15 percent of people with schizophrenia were “treatment resistant,” according to the psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey, the author of the 1983 book Surviving Schizophrenia: A Family Manual. “Treatment resistant” referred to patients who weren’t helped by medication, not those who resisted taking it. That percentage was much higher than 15 percent, in part because the conviction that you weren’t sick was often an aspect of the illness, especially at times of acute psychosis.

Before Michael’s psychotic break tipped the balance one way, and medication tipped it back the other, he had seemed to both know and not know what was happening to him—a state strangely mirrored by those around him, who had also recognized and ignored his illness by turns. I’d experienced for myself how rational his reasoning manner made unreasonable things appear. Ruth and Chuck had helped Michael install debugging devices on his phone, and by the time they realized that they’d been played by his delusions, he’d reclassified them as double agents.

I felt sadness when I saw Michael struggling through an intermediate existence after he got out of the hospital. His slowed speech, stiff formality, and dark suit, a hand‑me‑down from his former self, made me think of an undertaker in an old movie. I also felt sympathy, aversion, affection, and fear in unfamiliar and shifting combinations. When I saw him on Mereland, his collar was half up and half down. I wanted to smooth it down for him, or lift up the other side, but did neither.

Halfway

Michael moved into a halfway house in White Plains called Futura House. Suburbs didn’t like halfway houses or group homes, and New York suburbs had been very successful at excluding them. Michael’s mother said he was lucky to get into one, given how many fewer spaces there were than people seeking them.

The real trouble with halfway houses was that they were short‑term solutions for people with long‑term needs. Residents might do everything expected of them, take their medication, and follow all the rules, and still not be ready to move on after the one‑ or two‑year limit.

Supportive housing that combined psychiatric and social services with affordable lodging hardly existed at the time. People might shuttle between transitional housing, a family home, a hospital, a board‑and‑care facility, the home of a different relative, followed by another hospital, though never for long. Federal benefits excluded state hospitals, creating an incentive for states to offload costly patients. The process would start again, but never moving in a straight line as it followed the course of an illness that waxed and waned, and responded better or worse to medication at different times. The disability checks Michael received, and the Medicaid payments he was eligible for, did not create a community, let alone a caring one. Checks and pills were what remained of a grand promise, the ingredients of a mental-health-care system that had never been baked but were handed out like flour and yeast in separate packets to starving people.

Most of Michael’s disability check went straight to the halfway house. He was poor, he said, and not in a temporary or bohemian way.

As part of its congressional testimony in the 1980s about the crisis in care for people with schizophrenia, the National Institute of Mental Health prepared a chart showing that only 17 percent of adults with schizophrenia were getting outpatient care; 6 percent were living in state hospitals, 5 percent in nursing homes, and 14 percent in short‑term inpatient facilities. That left a full 58 percent of the schizophrenic population unaccounted for. Would Michael end up among the lost population?

Michael didn’t like Futura House, but he still heard its loud clock ticking. Every few months, he had a “resident review,” where counselors talked about a “life plan” and “vocational readiness.” (Futura House and the day program at St. Vincent’s Hospital had relationships with local businesses.) The counselors emphasized small steps, low stress, and a noncompetitive environment. Not necessarily forever, but definitely for now. One possibility, endorsed by the psychiatrists at the hospital, was for Michael to work as a cashier at Macy’s, a suggestion that fell like a hammer blow of humiliation.

Michael told the story of his father taking him to Macy’s, where they watched beleaguered clerks get pushed around by impatient customers, as an epiphanic moment. The verdict was clear: Yale Law School would be a lot less stressful.

Prometheus at Yale

For the network watching over Michael, choosing Yale Law School was a no-brainer. He might be suffering from a thought disorder, but his brilliance would save him. Michael agreed: “I may be crazy,” he liked to say, “but I’m not stupid.” It was hard to believe that Michael could go straight from a program of slow steps and daily skills, like using a checkbook and planning a meal, to the top-ranked law school in the country. But if you agreed that Macy’s would destroy him, it followed that Yale would set him free. I believed this. Michael’s parents believed this. So did the law school’s dean, Guido Calabresi, and the professors who became Michael’s mentors.

Michael was as quick to tell his professors about his schizophrenia as he was determined to keep it from his classmates. He made it clear that he didn’t want sympathy or special consideration, and his professors, who understood that he was asking for both, were deeply affected by his intelligence and vulnerability.

He told them how he awoke each morning to find his room on fire, lying in fear until his father called to convince him that the flames weren’t real. “Does it burn?” his father asked after telling him to put out a hand. “Does it burn? No? Good!” Then he ordered Michael to do the same with his other hand. “Is it hot? Does it burn? Does it burn?” Little by little, until Michael was standing upright on the burning floor.

His professors all heard the story of the burning room and repeated it to one another as a parable of his struggle and strength. He was like Prometheus having his liver eaten by an eagle every morning, growing it back every night in time to be tortured again at dawn.

It was a feature of Michael’s confessional style that his account of disabling mental illness communicated extraordinary mental ability, so that even after his professors realized he could not do the work, their sense of his brilliance remained. As one of his mentors later explained, many of the law school’s real success stories didn’t become lawyers at all. He thought Michael could be an eloquent advocate for people with schizophrenia, someone who had been to Yale Law School rather than someone who was a Yale lawyer.

But Yale lawyer was a phrase Michael already applied to himself. Recalling his struggle with the day-program doctors, Michael would say: “Why would I bag groceries when I could be a Yale lawyer?” Becoming a Yale lawyer was the whole point.

The Laws of Madness

Michael and Carrie had overlapped as undergraduates but began dating when Michael was in law school and Carrie, a literature major with a knack for computers, was living in New Haven and working for IBM. The mutual friend who brought them together loved and admired them both, but had doubts about them becoming a couple. He had lived with Michael his first summer during law school and remembered asking his roommate through a locked door if he wanted to come out for dinner, only to learn that Michael feared that he would be on the menu.

Michael waited months before telling Carrie he had schizophrenia; if she suspected something before that, she didn’t say. She wouldn’t have been the first person to not notice, or to ascribe symptoms such as surface tremors and apocalyptic utterances to the hidden depths of a complex soul.

Carrie wept when Michael told her. She did not reproach him for having kept his illness a secret. She showed no anger or fear or regret, only pain for his pain. She wept at the unfairness of what he had suffered in the past and was still suffering. She knew it was a terrible illness, but she loved him, and that was that.

Michael’s dream was to be a professor at Yale. He reported proudly that the law school had created a postgraduate fellowship just for him, in recognition of his genius. But there remained a certain gap between his ambitions and his mentors’ hopes for him. “I have thought to myself from time to time,” one of Michael’s professors told me: “Gee, if I hadn’t been so busy being proud of what a great place the Yale Law School was to have admitted Michael Laudor, I might have paid closer attention to him.”

When Michael began applying for teaching jobs, he was unable to explain in interviews why he had never clerked for a judge or worked at a law firm beyond a single summer that had not gone well. Advised to avoid any mention of schizophrenia—a “career killer”—Michael said that such work lacked the intellectual stimulation he required. He got no offers at all, a bitter setback.

But in the fall of 1995, while Michael was still mourning his father, who had died of cancer, something happened that changed his fortunes almost overnight. On November 9, The New York Times ran an article called “A Voyage to Bedlam and Part Way Back.” A second headline modified the first: “Yale Law Graduate, a Schizophrenic, Is Encumbered by an Invisible Wheelchair.”

The reporter, Lisa W. Foderaro, offered a sort of alternative résumé: “Mr. Laudor, 32 and by all accounts a genius, is a schizophrenic who emerged from eight months in a psychiatric unit at Columbia‑Presbyterian Medical Center to go to Yale Law School.” The story centered on Michael’s newfound determination to find a job as a law-school professor without denying or disguising his schizophrenia.

When Michael came out of the closet, he came out all the way. “Dubbing himself a ‘flaming schizophrenic,’ ” Foderaro wrote, “Mr. Laudor said that his decision to make his illness public and work closely with others with mental disabilities was a political and religious one.”

It was a glowing profile that captured Michael’s wry sense of humor (“I went to the most supportive mental health care facility that exists in America: the Yale Law School”) as well as his knack for harrowing formulations: “My reality was that at any moment, they”—the Nazi doctors—“would surgically cut me to death without any anesthesia.” He recalled the pain of his hospitalization with touching frankness: “I spent my 26th birthday there crying on my bed.”

He poured his private life onto the pages of the Times, confiding even his experience of the interview with liberated eloquence: “I feel that I’m pawing through walls of cotton and gauze when I talk to you now,” Michael told Foderaro. “I’m using 60 or 70 percent of my effort just to maintain the proper reality contact with the world.”

[Read: Can you cure mental illness? Two centuries of trying says no.]

Brilliance was the fulcrum of the story, the point at which Michael was lifted above the stereotypes of schizophrenia, much as intelligence had elevated him above ordinary expectations before he got sick. “Far from knowing that Mr. Laudor had a severe mental illness,” Foderaro wrote, “the other students were somewhat in awe.”

The article threw into stark relief the indignities of interviewing for jobs. “One interviewer asked if he was violent,” Foderaro wrote, “which Mr. Laudor said reflected a common and painful stereotype.” I understood Michael’s indignation, but I also knew that before he was medicated, Michael had armed himself with a knife in fear of his impostor parents. I wished the article had addressed the question even a little instead of leaving it to Michael to dismiss in a way that made you feel as if even to ask was an insult.

One of the things that haunted me about Michael’s breakdown was how frightened his parents had been. Without a father capable of bluffing and threatening Michael into signing himself in for his own good, he might not have gotten those eight months of care he’d so desperately needed.

Michael sounded exhilarated and slightly manic when we talked on the phone that winter. Book editors were in a bidding war for a memoir Michael was going to write, called The Laws of Madness, which was also going to be a Ron Howard movie. The deals would net him more than $ 2 million.

Like the Times profile, his 80‑page book proposal caused an electric stir. How often did anyone narrate schizophrenia from the inside out? Michael described what it had felt like to discover that his parents were evil imitations of themselves: “I soon burst in at 3 in the morning to accuse my parents of being impostors, of having killed my real parents while they themselves were neo‑Nazi agents altered by special surgery and trained to mimic my parents.”

The tone was reminiscent of countless sci-fi stories Michael had summarized for me in the schoolyard—he’d seen a secretary at Bain with “blood dripping from her teeth as her clawed hands reached for me”—but the proposal rose from the depths of such delusions, tracing the archetypal tale of a young man’s triumph and a father’s love. Even as it offered glimpses of bloody fangs and Nazi spies, the narrative arc bent toward Yale Law School. Michael’s agent escorted him to publishing houses, where he spoke with undaunted fluency.

When an editor asked Michael if he still hallucinated, he told her, “I’m hallucinating right now.” The room grew quiet as Michael described a burning waterfall emptying into a lake of fire. He also saw a peaceful house with shutters and vines. Michael explained that he managed these and other competing images by arranging them on a great screen in his mind, in a hierarchy of terror from greatest to least.

The movie people found his method of controlling his hallucinations a perfect cinematic conceit.

Michael made little progress on his memoir, possibly none. The movie, meanwhile, raced along like the river outside the window of his apartment in Hastings-on-Hudson, where he had moved with Carrie. It wasn’t the first time a screenwriter had needed to base a movie on a book that didn’t exist. It could even be an advantage.

But for Michael, leaving his story to Hollywood was unthinkable. The closer The Laws of Madness got to becoming a movie, the more important the book became, a chance to restore the dream of creative achievement that had gone up in smoke.

In an effort to bolster Michael’s resolve, his editor Hamilton Cain took the train to Hastings‑on‑Hudson. Cain brought a tape recorder, hoping an interview might jump‑start the process. He and Michael envisioned a series of sessions.

The interview began with Michael talking about Mereland Road and me: “There were only six or seven houses in the most immediate part of our neighborhood, our street. I was inseparable from a friend who moved in when I was in fifth grade, Jonathan.” We were both going to be writers, he told Cain: “He’s done it; he is a novelist. I was sure that I, too, would be one.”

Cain and Michael talked all day. The apartment grew dim as the December sun crossed the river and disappeared behind New Jersey. Michael had never turned on the lights, and made no move to do so as the winter dusk crept inside. Cain was scribbling in the interior gloom, eager to capture a few last thoughts from what he felt had been a very successful session. Suddenly Michael spoke in a voice that seemed to have dropped an octave. Startled, Cain looked up and saw Michael, still sitting across from him, rocking back and forth.

“I’m very tired,” Michael said in a deep, denatured voice. “I think you’d better go.”

“We’ll wrap it up,” Cain said, turning back to his notebook. He was scribbling fast when he became aware that Michael had risen and come over to the couch where Cain was sitting. He sensed his looming presence, rocking back and forth. Cain felt the hairs on the back of his neck stand straight. Michael was towering over him, his face utterly transformed.

“Is everything okay?” Cain asked.

“I think you should go now,” Michael said, his voice deep and slow. “I’m really, really tired.”

Cain was all speed, gathering up his tape recorder, notebook, backpack, coat, but by the time he was at the door saying good-bye, Michael had recovered his old self and insisted, with customary gallantry, on walking him to the train station. He talked easily on the short walk, and at the platform gave Cain a hug.

Neither of them mentioned the anomalous moment in the gloom. Still, the impression troubled Cain, and stayed with him on the train back to the city.

“We Can’t Do Anything”

To the seasoned observers of the Network watching over Michael, his relationship with Carrie was one more example of his exceptional nature. In their experience, it was unusual for people with schizophrenia to sustain long‑term relationships.

For Carrie’s colleagues, the equation was reversed: Michael’s illness was evidence of Carrie’s exceptional nature. But she did not like to talk about the times when she came home from work and Michael refused to let her into their apartment, because he didn’t believe she was who she said she was. No matter how much Carrie insisted, she couldn’t convince him of the truth. How could he trust her words when he didn’t believe it was her body? At such times, the terror and fury on the other side of the door were enough to send her to a friend’s couch. Those were hard nights.

That the tough times were getting worse was no secret to the members of the Network, who now watched over Carrie as well.

One evening in June 1998, Jane Ferber had dinner with her friend Myrna Rubin and conveyed her distress about Michael’s backward slide. Myrna had heard that Michael had stopped taking his medication and that nobody had been able to get him to go back on it, but she was shocked when she heard that he thought Carrie was an alien. Still, delusions were no more a justification for forced medication than refusing medication was a justification for forced hospitalization. The only question was whether Michael was violent, and the Network didn’t see him that way.

Elizabeth Ferber, Jane’s daughter, had been hearing reports about Michael’s decline from her mother. That he was losing control was disturbing, but it was the constrained intensity of her mother’s voice, the sadness and resignation, that affected her most. Surely now was the time to act.

But when Elizabeth demanded to know what was being done, her mother told her, “We can’t do anything.”

What Elizabeth heard in her mother’s voice wasn’t fear of Michael, but fear for him. The danger that weighed most heavily on the members of the Network was that Michael would suffer a break from which he might never recover—that he would end up in the revolving door of endless hospitalizations. They doubted the efficacy of the system but feared its capacity for destruction, and they desperately wanted to save him from it.

On Wednesday, June 17, the day before her work team was flying to Chicago for a big meeting, Carrie called her office to say she had a personal emergency and would not be coming in. It was unusual for Carrie to miss a day of important preparation, but her boss had no doubt she would be there the next morning with her materials in order.

Too Late

It was a day of frantic phone calls and failed efforts at intervention. Michael had been bombarding his mother, making wild accusations and irrational threats. After Michael ranted about suicide and murder, Ruth called back in a panic. Michael picked up, and Ruth told him to give the phone to Carrie. Michael said he couldn’t do that, because he’d killed her.

Ruth called the police at 4:17 p.m. She urged speed and gave few details. The desk sergeant heard the panic in her voice and put out a radio call to check on the welfare of a couple in the River Edge apartments.

Officers rang Michael and Carrie’s bell and got no response. The door was locked, so they radioed their sergeant, who called Lieutenant Vince Schiavone, the department’s executive officer, at home. Schiavone told them to get the key from the super and check out the place at once.

The officers found a woman’s body in the kitchen, lying in a pool of blood. There were multiple stab wounds, and her throat had been cut. Schiavone visited the crime scene briefly, then drove with an officer to New Rochelle to deliver the news to 28 Mereland Road in person. Ruth peered through the glass, opened the door, and asked, “Is she …?”

“Yes,” Schiavone told her. “She is.”

Ruth burst into tears. Schiavone would never forget the look on her face. It seemed to say, Oh my God, we didn’t move fast enough.

“I knew something like this could happen,” Ruth said, explaining that her son had schizophrenia. “But he was getting happy. They were going to be married …”

Her anguish was intense. They’d been trying to get him the help he needed, she said. Not that he wasn’t getting help already. She wanted Schiavone to know, he felt, that they’d been working on this, and it had gotten away from them somehow.

The medical examiner’s report, released quickly, told its stark forensic story. The death was a homicide. The cause was “sharp force injuries of head, neck, back and upper extremity involving lungs, aorta, esophagus and thyroid cartilage.”

An additional piece of information deepened the tragedy: Carrie was pregnant.

Michael’s photo was on the cover of the New York Post under a massive one‑word headline, printed in white-on-black “knockout type”: PSYCHO.

Seeing Michael looking out from the far side of that tabloid window like the Son of Sam was shocking. The photo filled the left side of the page; the right half announced, also in white‑on‑black type: “Twisted genius charged with savage slaying of pregnant fiancee.” At the bottom right was a picture of Carrie smiling with hopeful innocence. A footer running the width of the page flagged coverage of Michael’s ill‑fated movie: “Universal Studio honchos on hot seat page 32.”

Michael was charged with second‑degree murder. Because of the nature of the crime, no bail was set. But Michael’s lawyer did request that Michael receive psychiatric treatment. Now that he’d killed someone, it was no longer necessary to prove that he was an imminent danger to himself or others—he could finally get the care and medication he needed. The state, eager to have him fit to stand trial for murder, would provide him with both.

“Untreated Psychosis Kills”

A month after Carrie’s killing, another gruesome event eclipsed and extended Michael’s story. A 41-year-old man named Russell Weston Jr. walked into the Capitol in Washington, D.C., and shot a police officer in the back of the head with a .38‑caliber revolver. He exchanged shots with another officer, wounding him and a tourist, then raced down a corridor and through a door that led to a suite of offices used by Majority Whip Tom DeLay, where he shot a plainclothes detective in the chest, killing him.

It did not take long to discover that Weston had rejected treatment for paranoid schizophrenia and was severely delusional. He had stormed the Capitol to access an override console for the Ruby Satellite System, stored in the Senate safe, which was the only way to avert the cannibal apocalypse and plague that were about to destroy the world.

Despite their radically different backgrounds, Michael Laudor was immediately joined to Russell Weston: Both suffered from a severe mental illness, had rejected medication, and in the grip of psychosis had killed people.

Torrey, the psychiatrist, wrote about the two men for The Wall Street Journal in an article called “Why Deinstitutionalization Turned Deadly.” The stories of the “Yale Law School graduate” and the “drifter,” the psychiatrist wrote, “are only the most publicized of an increasing number of violent acts by people with schizophrenia or manic‑depressive illness who were not taking the medication they need to control their delusions and hallucinations.”

Weston’s anguished father, Russell Sr., was quoted in a New York Times column about the impossibility of helping his son: “He was a grown man. We couldn’t hold him down and force the pills into him.” Weston’s father could do nothing, Frank Rich wrote, because “a comprehensive system of mental‑health services, including support for parents with sick adult children who refuse treatment, doesn’t exist. If it had, the Westons might have had more success in rescuing their son—as might the equally loving family of Michael Laudor.”

For politicians, the outrage of after was easier than the work of before. President Bill Clinton denounced the violence of an unmedicated psychotic man nobody felt authorized to treat as “a moment of savagery at the front door of American civilization.” Diagnosed in his late 20s, Weston had spent 53 days in a state hospital in 1996 after threatening an emergency-room worker. Once he no longer seemed imminently dangerous, he had been released with pills that he eventually stopped taking, perhaps because he did not consider himself mentally ill.

“The total number of individuals with active symptoms of schizophrenia or manic‑depressive illness is some 3.5 million,” Torrey wrote. “The National Advisory Mental Health Council has estimated that 40% of them—roughly 1.4 million people—are not receiving any treatment in any given year. It is therefore not a question of whether someone will follow Michael Laudor and Russell Weston into the headlines. It is merely a question of when.”

Torrey did not see Michael’s killing of Carrie as a “tragic inevitability,” which is how the law professor who had once imagined Michael becoming an advocate for people with schizophrenia described it to me years later.

Nor did Torrey believe that the 1,000 annual homicides he attributed to people with severe unmedicated mental illness should indict the population of those with similar diagnoses. But he did want to prevent those homicides, as well as an even larger number of suicides, and he wanted to reduce the growing number of mentally ill homeless people, and do something about a prison population swelled by people suffering from mental illness who received no care. His sister had schizophrenia, and he did think there was a difference between being in your right mind and being out of it.

The arguments Torrey made about Michael in The Wall Street Journal in 1998 informed the Treatment Advocacy Center, which he created that year to focus on the medical, moral, and legal imperatives of treating people whose severe mental illness prevents them from knowing they need help. Now 85, Torrey was recently profiled in The New York Times, which credited him with inspiring assisted outpatient treatment programs—present in 47 states—as well as Mayor Adams’s new initiative and a larger transformation in the understanding of severe mental illness at the policy level.

Last spring, Adams appointed Brian Stettin, who had been working as the Treatment Advocacy Center’s policy director, to be his administration’s senior adviser on severe mental illness—a title that itself announces a policy shift. Adams hired Stettin not long after he published an op-ed in the Daily News about the death of Michelle Go, who had been pushed in front of a subway train in January 2022 by a man who’d been hospitalized more than 20 times.

Stettin noted that the man who killed Go should have been in an assisted outpatient treatment program, but had fallen through the holes of a porous system. He began his article by recalling Kendra Webdale, who also had been pushed in front of a subway train and killed 23 years earlier. A young assistant attorney general at the time, Stettin had been tasked by his new boss, New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, with drafting legislation to prevent horrors like the one that had befallen Webdale. Her killer had been hospitalized 13 times in two years and on one occasion had literally walked into Bellevue Hospital demanding help. The man, who suffered from severe mental illness, wanted to return to housing on the grounds of Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, in Queens, but to qualify, he would have to be hospitalized there first, and he couldn’t be hospitalized, because no beds were available. He was given the phone number of a mobile crisis unit by a social worker, who noted that he had no phone.

When they asked Webdale’s parents to lend their daughter’s name to legislation creating assisted outpatient treatment programs across New York State, Spitzer and Stettin discovered that the family had received letters of support not only from parents who had lost children to violence but from parents who had written to say of the killer, “That might have been my son.” Webdale’s mother wanted to know what the attorney general was going to do for those parents.

I experienced something similar when I spent time with Nick and Amanda Wilcox, whose daughter, Laura, a 19-year-old sophomore at Haverford College, was killed in 2001 while working at a mental-health clinic during her Christmas break. Laura’s Law is California’s version of Kendra’s Law, passed county by county with the tireless support of the Wilcoxes, who faced opposition from the ACLU and fellow Quakers, who consider assisted outpatient treatment programs a threat to civil liberties.

It was heartbreaking to stand in Laura’s childhood bedroom and hear the terrible comfort the Wilcoxes took in learning that the pen their daughter had gripped so tightly in death suggested that she had died instantly. I knew they had refused to seek the death penalty for their daughter’s killer—who killed two more people at a nearby restaurant, where he believed he was being poisoned. But hearing them say “He’s in the right place”—a state mental hospital—after he was found not competent to stand trial, and realizing it was treatment they wished for him, was a humbling astonishment. The anger they expressed was directed at a system that had resisted committing a severely ill, dangerous man known to have an apartment filled with unregistered guns, in part to avoid the cost of sending him to a county with a suitable facility.

I was the childhood friend of someone who had killed a woman not unlike the Wilcoxes’ daughter. Amanda gave me advice about reaching out to Carrie’s parents. “Say you’re sorry for what your friend did,” she told me. “That’s what I would want to hear.” Although Carrie’s family wrote back to tell me it was simply too painful to talk about, I was grateful I’d been able to express my sorrow.

E. Fuller Torrey sees what is happening in New York and California—where Governor Gavin Newsom has signed the Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Act—as part of a sea change. He has no illusions about the challenges—New York State still hasn’t recovered all of the 1,000 psychiatric beds repurposed for COVID use during the pandemic—but he believes that change starts with the recognition that denying care to people too impaired to know they need it is a medical and moral failure. He thought it a hopeful portent that when a disability-rights group tried to block the CARE Act, the group’s Sacramento offices were picketed by relatives, friends, and other supporters of people with severe mental illness carrying signs saying UNTREATED PSYCHOSIS KILLS and HOSPITALS NOT PRISONS. When I asked Torrey what he considers the biggest threat to reform, he said pessimism, the resigned conviction that after 40 years of failed efforts, nothing can be done.

Katherine Koh is a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital. As part of the street team at the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, she works with the most neglected population in the country, people struggling to meet basic needs even if they are not suffering from a mental illness. Though she spoke of involuntary commitment as “a difficult, nuanced, and thorny issue” that “haunts and plagues” her, she told me that the biggest improvements in people’s mental health can happen when they are involuntarily hospitalized, provided there is a plan in advance and care afterward.

Koh also told me a story that she’d heard from her mentor, Jim O’Connell, the founding physician at Boston Health Care for the Homeless. The story is about a woman he spent many years caring for on the street, who was often on the psychiatric brink, though O’Connell, determined to honor her autonomy and dignity, never committed her. Finally, the police did it for him. After the hospital, and time spent stably housed, the woman moved on to other systems of support, slowly recovered her balance, began working again, and eventually joined the board of an organization that sponsored the event where she and O’Connell reunited after many years. When the woman saw him—as Koh recalled her teacher’s vivid recounting—she said, “You son of a bitch! You left me out on the street for 10 years!” And then a further lesson: “If I were bleeding, you would have taken me in. But since it was my brain, you left me out there.”

Laurie Flynn, who was the executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness when Michael killed Carrie, burst into tears when she learned what had happened. Michael had been a hero to many at NAMI, the largest grassroots organization in America dedicated to supporting people with severe mental illness and their families. He had seemed so emblematic of a new era, promising the rejection of shame and stigma, that the “Michael Laudor Tragedy,” as Flynn called it, became part of a complex reckoning that filled many in the organization with the understandable fear of stigma.

Violence and mental illness have been legally entangled ever since dangerousness, rather than illness, became the de facto prerequisite for hospitalization. If a hospital could produce a bed, or mandate treatment, only for someone actively threatening harm, you could hardly blame the general population for mixing up the very sick and the very violent, or mental hospitals and prisons. Today the Twin Towers Correctional Facility, in Los Angeles, is described—by the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department—as “the nation’s largest mental health facility.”

And you can hardly blame advocates for wanting to erase even the suggestion of violence as a precondition for eliminating stigma. But denying all distinctions can be as destructive as exaggerating them. Many of the critics of Adams’s proposal highlighted the involuntary hospitalization of mentally ill people “even if they posed no threat to others,” as if hospitalizing a gravely ill person who didn’t threaten someone’s life made no sense.

For Flynn, the problem is a system that forces families to “sit and watch someone they love deteriorate, unable to get them help until they are dangerous.” Acknowledging distinctions, in order to address people’s needs, will do more than denial does to reduce stigma. It will also keep people alive.

In the Daily News op-ed, Stettin wrote, “There are fundamental differences between the 4% of the population with severe diagnoses and the rest of us who experience various mental health challenges over the course of our lives. A big one is that without treatment, people with severe mental illness lose their connection to reality.” He is at pains to emphasize that the mayor’s initiative is directed at a fractional subset of that percentage, people without shelter who are too sick to care for themselves or recognize their own impaired condition.

It has been 25 years since Michael killed Carrie. For most of that time, he has been in a secure psychiatric facility surrounded by a 16‑foot‑high fence topped with razor wire. He lives with 280 other men and women sent there by court order, attended to by twice that number of staff.

Michael was found not responsible by “means of mental defect,” bolstered by the finding of Park Dietz, the forensic psychiatrist hired by the prosecution, who was known for his narrow definition of insanity. Dietz had found both John Hinckley and Jeffrey Dahmer legally sane, but he determined that Michael truly thought he was killing a doll or a robot.

I know there is no going back to the time before Michael killed Carrie, just as there is no going back to the monumental hospitals that long ago ceased to be worthy of the concept of asylum that created them. Just as there can be no going back to the utopian vision of the people who destroyed them, whose faith in their own expertise and dream of community care failed to fulfill their promise to the people whose desperate need had justified the demolition.

I also know that there can be no going forward without a reckoning, however partial and imperfect. Not to apportion blame, but to make it easier to change or clarify a law, or to narrow the focus of an initiative—while expanding its resources—to address a fraction of the population whose illnesses are so severe, they can make sufferers unaware of their own deterioration. Above all, it should be harder to impose imaginary solutions on real problems.

Two years before Michael killed Carrie, a Times article had quoted him, identified as a legal scholar with a history of schizophrenia, expressing outrage that a medical student—who had stopped taking medication for his bipolar disorder and was alarming psychiatrists and fellow students with what they considered violent and threatening behavior—had “lost five weeks of his life” to forced hospitalization. The article was called “Medical Student Forced Into a Hospital Netherworld,” but who among Michael’s friends would not wish now that the same had happened to him, if five weeks could have helped return him to the treatment he needed, saved Carrie’s life, and prevented Michael’s destruction?

I remain haunted by my last phone conversation with Michael before he killed Carrie. He was vague, equivocal, even as we picked a date to see each other that I suspected, perhaps hoped, would pass like the others. “I have to go,” he said abruptly. “I’m having bad thoughts I need to not be having.”

I knew something was dreadfully wrong, but I buried that abject statement, and kept myself from considering its meaning.

This article has been adapted from Jonathan Rosen’s forthcoming book, The Best Minds: A Story of Friendship, Madness, and the Tragedy of Good Intentions. It appears in the May 2023 print edition with the headline “American Madness.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.